- Brooklyn rapper says he hopes to be known for his music with "Prisoner of Conscious"

- Talib Kweli rose to prominence as half of Black Star, later developed reputation for lyricism

- Socially conscious rap, he says, can be "pretentious and corny and condescending"

(CNN) -- Call it Talib Kweli's jailbreak.

While that might mean something different for some rappers, Kweli, 37, sees his latest project as a way to escape the box the music industry and casual hip-hop fan have placed him in.

The "conscious rapper" category is meant for the socially responsible hip-hop artists who don't see misogyny and violence as integral to cutting a track, even if it's handy in climbing a chart.

"I have kids, and I feel like there are a lot of young people listening to hip-hop, and they need to hear both sides of it," the married father of two said, adding that if one segment of rap music wants to revel in the negative, "I'm going to say something that I feel is relevant to right now, try to provide you with a balance. I'm a Libra. I believe in balance."

Kweli's new album, "Prisoner of Conscious," is named after the term coined to describe those jailed for their race or ideas. But don't get caught up in the shout-outs to Azerbaijani activist Tural Abbasli, Iranian human rights lawyer Nasrin Sotoudeh, various Black Panthers and other prisoners around the world.

Samsung teams with Jay-Z on CD freebie

Samsung teams with Jay-Z on CD freebie

Wiz Khalifa on Snoop Dogg and marijuana

Wiz Khalifa on Snoop Dogg and marijuana

Lil' Wayne steps on flag in video shoot

Lil' Wayne steps on flag in video shoot

Lauryn Hill's fall from grace

Lauryn Hill's fall from grace

While Kweli feels a kinship with imprisoned Russian punk rockers Pussy Riot and others "who make art that resists against systems of repression," it's not what he's getting at with the album title.

Not just a lyricist

Say Talib Kweli to a hip-hop head and it won't likely conjure club bangers. It might not conjure music. Kweli is a pure lyricist -- smart, provocative, political and too rarely noted for his melody. As Jay-Z once rhymed in a backhanded compliment, "If skills sold, truth be told, I'd probably be, lyrically, Talib Kweli."

The Brooklyn-born rhymesmith takes umbrage with the idea he's a words-only artist. Kweli is quick to emphasize he's worked with top producers, including DJ Quik, the late J. Dilla, Pete Rock and Kanye West.

"I feel like I've worked with the best in the business and that's what's added to what I do. It's not just the lyrics," he said. "I think this might be my least lyrical album, I don't know, because the music was forefront for me on 'Prisoner of Conscious.' That's really what my focus is. I'm a musician at the end of the day."

Which may explain why "POC" is more radio-friendly than his last album, "Gutter Rainbows." Production assists from J. Cole and Wu-Tang's RZA don't hurt, and other current and former hitmakers such as Kendrick Lamar, Busta Rhymes and Nelly appear on the mic. But Kweli says he wasn't digging for a chart topper.

Hip-hop: Long on lyrics, short on rehab

"It was in sync with the theme of the album that I can do whatever I want to do. I'm not really a prisoner of any bias. ... It wasn't like, 'Oh, because Kendrick's hot.' I just try to choose artists that I really like and that I have a real good relationship with," he said, noting that the track with Lamar, "Push Thru," was made two years ago.

Releasing the album on his Javotti Media label afforded Kweli another luxury: time. Four years of it. He started work on "POC" when Lamar was still K-Dot.

"I approached it like, 'OK, this album's going to come out and it doesn't have to be on a schedule.' I can just work on it until I feel like it's done," he said

Talib Kweli

Most of his five solo and four collaboration albums took about a year, though "Gutter Rainbows" took three months, "Liberation" took a week and "Train of Thought" took about two years.

The extra time with "POC" allowed him to think more musically, which wasn't a stretch. He is, after all, responsible for the classic "Get By" and the Mary J. Blige collaboration, "I Try," both a la West. He also cut his teeth with DJ Hi-Tek -- as the more prominent half of Reflection Eternal -- and with the artist formerly known as Mos Def -- as the less prominent half of Black Star.

That was the late 1990s, early 2000s, when his songs routinely hit the top six on rap charts, albums the top 15. Reflection Eternal's "Move Something" reached No. 1.

Genetically conscious

Yet left to his own devices, and his more plainspoken, occasionally darker lyrics about street life, Kweli's ability to appease critics didn't translate to sales. To date, his most successful solo effort, 2007's "Eardrum," has sold in its lifetime roughly what West's "Yeezus" sold in its first day or two.

Does Kanye West have a God complex?

One might postulate that if Kweli focused more on music than message -- and maybe alluded to gunplay or spanked an underwear model with a champagne bottle in his songs -- he might fit more comfortably in the lucrative class of corporate hip-hop.

His DNA and upbringing might work against it, though.

A boarding school product, his parents are a professor and university administrator who named him the Arabic word for student and the Swahili word for truth, Talib Kweli Greene. His brother, a Yale grad, teaches law at Columbia. You could say conscious is in his genes.

Talib Kweli

Several artists -- including Common, Nas, K'Naan, Lupe Fiasco and Damian Marley -- have shared their thoughts on the "conscious" classification with CNN in the past, with only Common fully embracing it (Lupe embraced the label, if not a monolithic definition for it).

K'Naan said "conscious" implies a rapper's lyrics are more responsible or noble than those of his counterparts, a position to which he couldn't subscribe (Nas and Marley concurred).

"I think those artists hit it on the head. It's an emotional response," Kweli said. "Being called conscious is a great thing to be, but it's the connotations and preconceived notions that come with the buying audience about what conscious music can be."

Those notions include the sentiment that conscious rap can be "pretentious and corny and condescending." To a degree, Kweli agrees, but he doesn't see mainstream rap being any better.

"What's more condescending and corny than someone telling you how much more money they have than you and telling you basically, 'I don't care about poor people'?" he asked, "which is a large part of what you hear of corporate hip-hop on the radio."

'You have to be a hustler'

Kweli doesn't think the best music is making it to the airwaves these days. For an artist to get noticed without label connections (see: career trajectories of J. Cole and Meek Mill), they have to work just as hard at promoting as they do at creating, he said.

"It's not really a talent-based game right now. No one takes a gamble. In order for you to have music, you have to be a hustler," he said.

Photos: Hip-hop in the Dirty South

Talib Kweli

Kweli's no exception. He has a reputation as tireless in the studio and energetic on stage. And there are the lyrics: "I got a Glock in my brain/that baffle weapon inspectors like Saddam Hussein."

"When I look at the arc of my career, my focus is on lyricism, right? I own that," he said.

The guys at the top have hustles, too. Nas and Jay-Z, for instance -- and he's a fan of both -- decided like many other rappers they'd focus on painting pictures of their don-like lives.

"You hear it in their lyrics: a lot of lyrics about money -- sex, drugs and money and capitalism and greed," Kweli said. "Not to say that's what defines them as men, but that's what a lot of their music revolved around, the themes and the pathologies in the 'hood."

This is where Kweli's views are anything but black and white. He'd never include such content in his own rhymes, but he'd also never condemn another rapper for it, even when fans think he should.

"I don't buy that," he said.

Take Rick Ross, a correctional officer-turned-gangsta rapper who came under fire this year for lyrics glorifying date rape.

Kweli said that Ross, as revolting as his word choice may have been, was a victim of circumstance while other rappers have skated for far worse lyrics. While Kweli would never condone date rape, or the Maybach Music boss' drug lord persona, he thinks focusing on that distracts from real problems in America's communities.

Talib Kweli

"He sounds like he's living the life of a drug dealer, but I see him putting out records. I think people get it twisted sometimes," Kweli said. "It's a little frustrating that people look at hip-hop with such a narrow lens, and sometimes hip-hop don't help."

Hip-hop vs. Hollywood

Kweli added that while music, movies nor video games will ever be the source of problems in black communities, "these things can perpetuate behaviors that are already there. ... The challenge is to not get distracted with looking at a symptom, which is negative music, and pretending that that's a root cause."

Virtual ODB, Eazy-E to take Rock the Bells stage

Rap is no different than Hollywood, he said. Rappers lie much like actors do, but where Hollywood is given a pass on fiction, hip-hop is expected to be authentic.

That makes rap an easy scapegoat when there are scarce answers to the poverty, poor education and general lack of opportunity in a community. It also provides a target when leaders won't or can't be held accountable. That isn't fair to the artists, Kweli said.

"Artists don't create an environment. Artists look at the environment, and the best artists correctly diagnose the problem," he said. "I'm not saying artists can't be leaders, but that's not the job of art, to lead. Bob Marley, Nina Simone, Harry Belafonte -- there are artists all through history who have become leaders, but that was already in them, nothing to do with their art."

If this kind of talk is indicative of Kweli focusing on the music and breaking out of the conscious rapper confines, he may need to start tunneling.

Talib Kweli, 37, began rapping in the mid-1990s and quickly became known for his provocative lyrical content. Here, he performs in Universal City, California, in 2005.

Talib Kweli, 37, began rapping in the mid-1990s and quickly became known for his provocative lyrical content. Here, he performs in Universal City, California, in 2005.

Kweli paired up with fellow Brooklynite Mos Def (now known as Yasiin Bey), right, to form the group Black Star. The pair's 1998 debut album, "Mos Def & Talib Kweli Are Black Star," is considered a classic.

Kweli paired up with fellow Brooklynite Mos Def (now known as Yasiin Bey), right, to form the group Black Star. The pair's 1998 debut album, "Mos Def & Talib Kweli Are Black Star," is considered a classic.

Kweli, here performing during the 2012 Sundance Film Festival, has never been as well-known as his Black Star counterpart, but he has gone on to release five solo albums and three more collaborations with other artists in addition to making guest appearances on albums and doing mixtapes.

Kweli, here performing during the 2012 Sundance Film Festival, has never been as well-known as his Black Star counterpart, but he has gone on to release five solo albums and three more collaborations with other artists in addition to making guest appearances on albums and doing mixtapes.

Kweli's only No. 1 hit to date, 2000's "Move Something," came after he joined forces with Cincinnati's DJ Hi-Tek, right, forming Reflection Eternal. The two would have several successful songs together.

Kweli's only No. 1 hit to date, 2000's "Move Something," came after he joined forces with Cincinnati's DJ Hi-Tek, right, forming Reflection Eternal. The two would have several successful songs together.

From left, Kweli, filmmakers Shukree Hassan Tilghman and Sharon La Cruise and activist Angela Davis at a Black History Month panel last year. The rapper often addresses the plight of African-Americans in his songs, once rhyming, "N****s with knowledge is more dangerous than n****s with guns/They make the guns easy to get and try to keep n****s dumb."

From left, Kweli, filmmakers Shukree Hassan Tilghman and Sharon La Cruise and activist Angela Davis at a Black History Month panel last year. The rapper often addresses the plight of African-Americans in his songs, once rhyming, "N****s with knowledge is more dangerous than n****s with guns/They make the guns easy to get and try to keep n****s dumb."

Asked if he agreed with Common, left, who told CNN in 2009 that Barack Obama's election

Asked if he agreed with Common, left, who told CNN in 2009 that Barack Obama's election  Kweli, pictured with his wife, DJ Eque, in 2009, says his two children listen to hip-hop, so he feels a responsibility to rap about more positive things to provide balance to the music genre's mainstream messages.

Kweli, pictured with his wife, DJ Eque, in 2009, says his two children listen to hip-hop, so he feels a responsibility to rap about more positive things to provide balance to the music genre's mainstream messages.

Kweli is often regarded -- even by Jay-Z -- as one of the best lyricists in hip-hop, but the kudos haven't always translated into album sales. He is shown in 2008 on the set of "Yo! MTV Raps" with host Cipha Sounds, right.

Kweli is often regarded -- even by Jay-Z -- as one of the best lyricists in hip-hop, but the kudos haven't always translated into album sales. He is shown in 2008 on the set of "Yo! MTV Raps" with host Cipha Sounds, right.

Kweli performs with Strong Arm Steady at New York's Apollo Theater in 2007. The self-described "ebony man/Apollo legend" released his early works with Rawkus Records and has since launched two labels, the now-defunct Blacksmith Music and Javotti Media, which released his latest album.

Kweli performs with Strong Arm Steady at New York's Apollo Theater in 2007. The self-described "ebony man/Apollo legend" released his early works with Rawkus Records and has since launched two labels, the now-defunct Blacksmith Music and Javotti Media, which released his latest album.

Kweli, here in 2003 with Kanye West, Common and Kevin Liles, then-executive VP of Island Def Jam, said he'd like hip-hop fans to know he has worked with the best. Among the big names on his new album are Busta Rhymes, Nelly, RZA and J. Cole.

Kweli, here in 2003 with Kanye West, Common and Kevin Liles, then-executive VP of Island Def Jam, said he'd like hip-hop fans to know he has worked with the best. Among the big names on his new album are Busta Rhymes, Nelly, RZA and J. Cole.

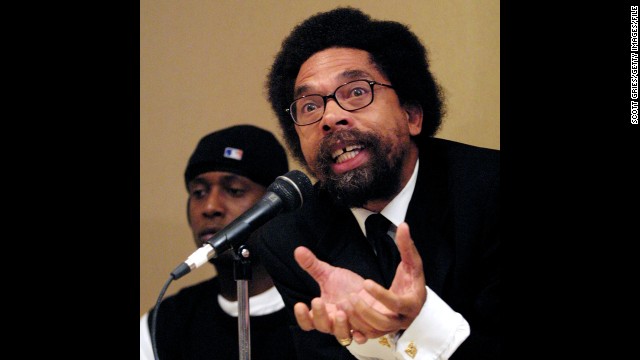

Pictured behind author Cornel West at the 2001 Taking Back Responsibility hip-hop summit, Kweli has always been known for the intelligence and thoughtfulness of his lyrics. With "Prisoner of Conscious," he'd like to be known for his music, too, he says.

Pictured behind author Cornel West at the 2001 Taking Back Responsibility hip-hop summit, Kweli has always been known for the intelligence and thoughtfulness of his lyrics. With "Prisoner of Conscious," he'd like to be known for his music, too, he says.

The bad news for Kweli's fans: "Black Star, at this juncture, is a live-only experience. ... We do a lot of shows, but there's no plans for a record or album or anything like that at this point," Kweli says.

The bad news for Kweli's fans: "Black Star, at this juncture, is a live-only experience. ... We do a lot of shows, but there's no plans for a record or album or anything like that at this point," Kweli says.