- New album by Jimi Hendrix coming out

- "People, Hell and Angels" tracks recorded in 1968 and 1969

- Hendrix "a maverick," his longtime engineer/producer Eddie Kramer says

- Despite innovations, Hendrix might have had a tough time breaking through today

(CNN) -- Jimi Hendrix has a new album, "People, Hell and Angels," out Tuesday.

So what, right?

Sure, the guitarist was a master, redefining the capabilities of the instrument. Yes, his songs and performances -- "Purple Haze," "Castles Made of Sand," "Voodoo Child (Slight Return)," the Woodstock version of "The Star-Spangled Banner" -- are classics.

But the guy's been dead for almost 43 years.

Before he died, he made just three studio albums: "Are You Experienced," "Axis: Bold as Love" and "Electric Ladyland." ("Band of Gypsys," a fourth album that came out just before his death in September 1970, was a live LP.) After that, thanks to various legal issues, there were dozens of albums put out in his name -- compilations, studio meanderings and more bootlegs than you'll find in a chorus line of lumberjacks. Diehards have them all.

And even if the legal details have been straightened out over the last few years -- the recent releases are far more meticulous -- rock music long ago moved on from Hendrix's tie-dye era, splitting into subgenres and sub-subgenres. The guitarist himself is now generally the subject of classic rock two-for-Tuesdays and some yellowing bedroom posters: a guitar-god statue, forever frozen in the act of lighting his guitar on fire.

So could there be any interest in hearing yet another Hendrix collection?

Actually, yes.

"Somewhere," the first single from "People, Hell and Angels," hit No. 1 on Billboard's Hot Singles Sales chart in mid-February. His record label expects the album to debut strongly on the Billboard 200 album chart, which means quite a few people still are willing to part with their pennies to own the latest Hendrix release.

The attraction, says Hendrix biographer Charles R. Cross, is simple: There's just never been anybody like Hendrix.

"Jimi Hendrix stood out not just for his guitar playing, but he was a great songwriter and a tremendous vocalist," says Cross, author of the 2005 biography "Room Full of Mirrors." "What he created with those three studio albums was so revolutionary that you look back and those are still very innovative albums. ... It was a full-meal deal with Jimi, not just one thing."

John Covach, a music professor and director of the Institute for Popular Music at the University of Rochester, adds that Hendrix's ear -- his ability to mesh feedback, backward recording and high amplification with rock's basic musical structures -- would be notable in any age.

And along with Eric Clapton, Hendrix helped invent that virtuoso we call the "guitar hero," he adds.

"After (them), every guitar player wanted to have a solo, and guitar soloing and virtuosity (were) thought of as a central feature of rock music," he says. "Before that, Keith Richards' guitar solos, George Harrison's guitar solos, Roger McGuinn's guitar solos -- (they were) not really features of the tunes." Perhaps some instrumental artists, such as Duane Eddy or the Ventures, had a little of that touch, he says, but it wasn't until the extended jams of Hendrix and Clapton that solos became a mainstay of rock.

'He really did think of the big picture'

"People, Hell and Angels" features 12 songs that Hendrix recorded in 1968 and 1969, many of which were intended for the studio follow-up to "Electric Ladyland." All of the songs are Hendrix originals with the exception of "Bleeding Heart," an Elmore James tune, and "Mojo Man." The musicians vary from song to song -- some with fellow Experience member Mitch Mitchell, others with longtime Hendrix pals Billy Cox and Larry Lee. Stephen Stills guests on "Somewhere."

Eddie Kramer, Hendrix's longtime engineer and producer, recalls the guitarist bringing in almost anybody he thought was interesting -- especially his friends from Britain, where he'd risen to fame practically within hours of arriving in 1966.

"He knew that a lot of the English guys would be jamming around the corner from the Record Plant," the studio in Midtown Manhattan where Hendrix often recorded. Hendrix would go to a nearby club and stay until after midnight, Kramer says, "checking out who was the cool musician or musicians who could accompany him and keep up to his standards." The list included such notables as Steve Winwood and the Jefferson Airplane's Jack Casady.

When the club jam session was over, Hendrix would invite the crew to the Record Plant. Kramer chuckles when thinking about those days: "You can imagine Jimi walking down Eighth Avenue, dragging 20 people, stopping traffic, walking into the Record Plant -- he walks in, rehearses once or twice, we record it, and it's done."

Indeed, Hendrix always had a plan in mind, Kramer says. He wasn't the studio doodler of legend, rambling for hours with nothing in mind.

"It's a bit of a myth. He really did think of the big picture," Kramer says. "You would think that those jams were loose. They were not -- they were planned. I've seen the notes, and I remember watching Jimi write out the notes on a big legal pad -- the construction of the song, where the drum breaks would occur, what the chords were, what the vibe of the track was. Even if it was a jam like 'Voodoo Child,' he had planned it weeks in advance."

"People, Hell and Angels" is testament to his work ethic, he adds.

"He was trying to find a new musical direction and wanted to step outside the Experience and get their input," he says. "That whole period he was testing the waters -- trying stuff with horn players, trying stuff with guys who were more into the jazz idiom. ... These are stripped-down versions of the songs, and they're really powerful. They really have a lot of guts."

The challenges of crossing over

For all of the accolades, Hendrix has received in the last four decades, he wasn't always celebrated while he was alive.

"Jimi is neither a great songwriter nor an extraordinary vocalist," wrote Jon Landau in a 1967 Rolling Stone review of "Are You Experienced." "The poor quality of (some of the) songs, and the inanity of the lyrics, too often get in the way" of the musicianship.

A year later, reviewing "Axis: Bold as Love" in the same magazine, Jim Miller echoed Landau. "Jimi Hendrix may be the Charlie Mingus of rock. ... But his songs too often are basically a bore," he wrote.

And even while a leader in the late '60s rock scene, he didn't always fit in. He was an African-American in an increasingly white musical landscape, a man who'd leapt from the chitlin' circuit -- the R&B clubs where he'd backed Slim Harpo, the Isley Brothers and Little Richard -- to headlining theaters where the Airplane and Traffic played. (And just before that, the Experience famously hit America by opening for the Monkees on a handful of 1967 tour dates.)

"To succeed with white audiences he had to achieve a balance," Cross writes in "Room Full of Mirrors." "Too much 'show' and he'd lose them. ... At the same time, Jimi needed a select few of those moves to establish himself as a showman because just being a talented guitar player -- black or white -- was not a ticket to stardom."

Today, in an era even more determined to put its musicians into distinct little marketing-approved boxes, a crossover artist such as Hendrix -- a black rock guitarist -- is even rarer. Gary Clark Jr., an African-American guitarist who's been compared to Hendrix, is filed under "blues," and has observed that he's aware he's going against a commercial grain that practically demands African-American musicians play hip-hop or jazz, and white musicians play blues or rock.

"For a black male, the sound of the blues is pre-civil rights. It's oppression," he told Vanity Fair. "In high school I had a friend who asked me why I played the blues, that black people don't play blues."

There have been attempts to crack those stereotypes, but if anything, it's even harder than it was in Hendrix's day, a time when AM Top 40 had plenty of variety, free-form FM radio welcomed experimenting and record labels strained to catch up with it all.

"I grew up listening to all the classic rock and being completely taken by two people the most -- Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin," says Sophia Ramos, 43, a member of the Black Rock Coalition, an organization co-founded by Living Colour guitarist Vernon Reid to foster the growth of black rock musicians. Until recently, Ramos focused on the rock world, whether fronting rock bands or singing backup on rock records.

She's faced the marketing problems first hand. In the '90s, she led a rock band called Sophia's Toy, whose debut record went unreleased by its label because, she was told, "there was no market for female rock 'n' roll singers." Even today, she blames the industry more than the fans for not being open to black rock musicians.

"That's the crazy thing that (affects) we people of color who do rock 'n' roll -- or who do any music that's not what we're supposed to be doing -- it's the industry. It's not the audience," she says.. "When it comes to the coveted spots of who are we going to push in the star machine, those that have the money and the means to do so rarely are going to look at a black artist and say, 'Yeah, I'm going to get behind that.' "

Ramos' new project is a show of ranchera and bolero music.

"I've put rock 'n' roll behind me," she says.

'He broke a lot of barriers'

Could Hendrix have broken out of such classifications these days? Kramer says he believes he could have. To borrow Duke Ellington's phrase, he was "beyond category."

"When I think of Hendrix, I put him in the pantheon of Charlie Parker, Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Louis Armstrong -- he really is in that league because his individuality was so strong and his message was so strong and his mastery of his instrument was so complete," he says. "He was a maverick. He broke a lot of barriers, musically and in every way."

But Covach wonders if the audience would have followed. Would people fill arenas and stadiums to hear a 70-year-old Hendrix play lengthy jazz solos? Would his albums still go platinum?

"What would probably have happened to Hendrix is he would have released a whole series of records and critics would say they're fantastic and he'd have his fans on the Internet -- but then he'd go out and do shows and do 'Purple Haze' and 'Foxy Lady,' " he says.

Different times.

But if there's a notable sign that Hendrix isn't ready for the classic-rock bin -- that "People, Hell and Angels" isn't just for baby boomers reliving Woodstock -- it's in the fans. Covach observes his students are fascinated by the guitarist, and biographer Cross says his 13-year-old son is a convert.

"There forever is a new crop of young guitar players (listening)," he says. "He's a rite of passage for any guitar player."

What they learn is that Hendrix isn't just about guitar pyrotechnics. Yes, he probably would have stood out in the YouTube age, thanks to his showmanship. But the reason his music continues to thrive is beyond that image of the guitar hero. It's the space between the notes.

"For me, it's always a thrill," Kramer says. "I go into the studio and pull up a tape, and Jimi's talking to me -- at the end of a take, he's saying, 'Hey, how about that take?' And I go, 'Yeah, yeah, yeah. Try it again.' But it always puts the hair on the back of your head up."

As Jimi Hendrix's engineer and producer, Eddie Kramer had a front-row seat on the famed guitarist's career -- and he made the most of it. Click through some of these moments provided by Kramer, and sample more music history at

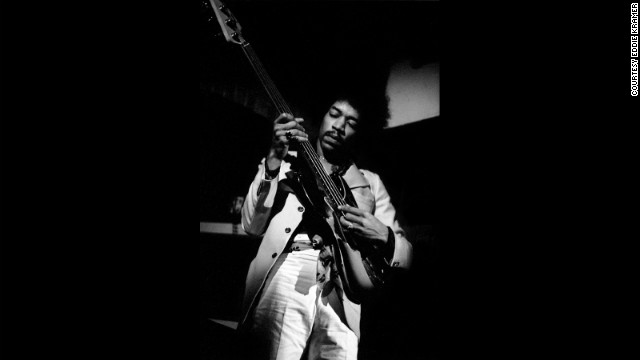

As Jimi Hendrix's engineer and producer, Eddie Kramer had a front-row seat on the famed guitarist's career -- and he made the most of it. Click through some of these moments provided by Kramer, and sample more music history at  Hendrix jams at The Scene club in New York in 1968:

"Jimi showing his prowess as an all-round musician playing Noel (Redding)'s bass upside down accompanying jazz guitarist Larry Coryell at The Scene club, which he used as his own personal rehearsal space trying out new ideas, testing musicians and making selections for possible inclusion in the recording of 'Electric Ladyland' just around the corner at the Record Plant on 44th Street." -- Eddie Kramer

Hendrix jams at The Scene club in New York in 1968:

"Jimi showing his prowess as an all-round musician playing Noel (Redding)'s bass upside down accompanying jazz guitarist Larry Coryell at The Scene club, which he used as his own personal rehearsal space trying out new ideas, testing musicians and making selections for possible inclusion in the recording of 'Electric Ladyland' just around the corner at the Record Plant on 44th Street." -- Eddie Kramer

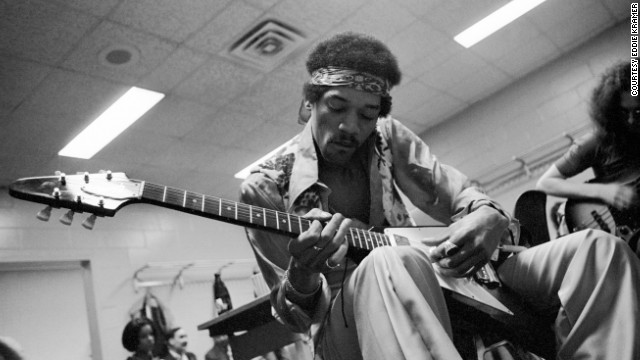

Hendrix relaxes and jams with Noel Redding at Madison Square Garden in New York in 1969:

"He often would rehearse quietly before going on stage with a small amp and his Flying V as it suited his style of playing the blues." -- Eddie Kramer

Hendrix relaxes and jams with Noel Redding at Madison Square Garden in New York in 1969:

"He often would rehearse quietly before going on stage with a small amp and his Flying V as it suited his style of playing the blues." -- Eddie Kramer

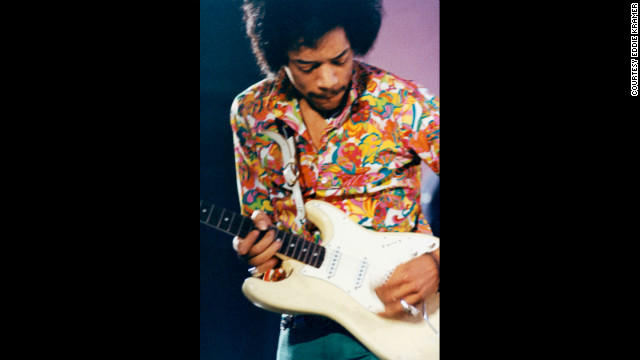

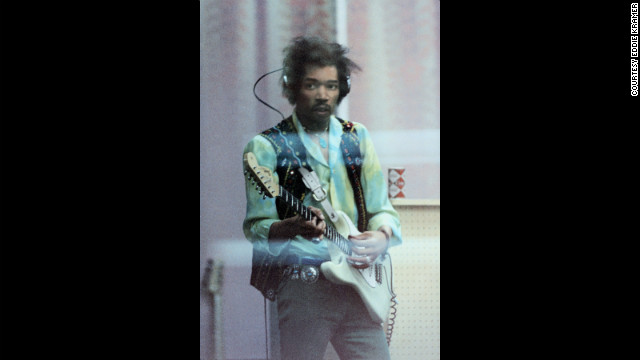

Hendrix records "Electric Ladyland" at the Record Plant in 1968:

"I had arrived in NYC to start work at the Record Plant in April of 1968 and jumped immediately into the recording of the 'Electric Ladyland' album. Jimi was in fine form and was always incredibly well-dressed, showing a taste for colorful shirts and green velvet pants." -- Eddie Kramer

Hendrix records "Electric Ladyland" at the Record Plant in 1968:

"I had arrived in NYC to start work at the Record Plant in April of 1968 and jumped immediately into the recording of the 'Electric Ladyland' album. Jimi was in fine form and was always incredibly well-dressed, showing a taste for colorful shirts and green velvet pants." -- Eddie Kramer

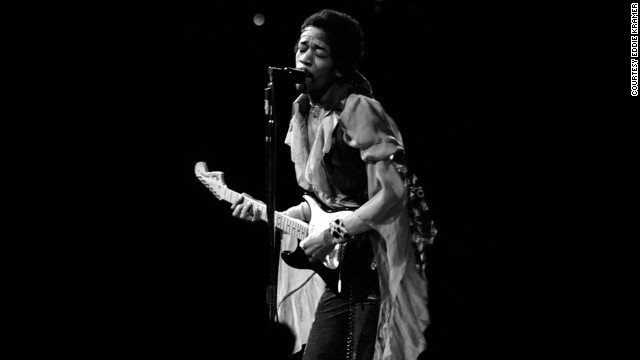

Hendrix performs at Madison Square Garden in 1969:

"I was always mesmerized by the transformation of Jimi's persona from the shy, soft-spoken individual into the towering monster guitarist that appeared on stage demolishing everything in his path with waves of intense sound. I rarely attended Jimi's shows as just a fan and not being in a mobile truck recording him,

so it was such a moment of visceral pleasure to capture these images from the side and front of the stage." -- Eddie Kramer

Hendrix performs at Madison Square Garden in 1969:

"I was always mesmerized by the transformation of Jimi's persona from the shy, soft-spoken individual into the towering monster guitarist that appeared on stage demolishing everything in his path with waves of intense sound. I rarely attended Jimi's shows as just a fan and not being in a mobile truck recording him,

so it was such a moment of visceral pleasure to capture these images from the side and front of the stage." -- Eddie Kramer

Hendrix records at the Record Plant in New York in 1968:

"Jimi was very self-demanding and a perfectionist. So when he heard back this particular solo, he was understandably pissed off at the result. His expression reminds me of a gunslinger about to knock off his next opponent ... except that it would be Take 29 of the overdub solo!" -- Eddie Kramer

Hendrix records at the Record Plant in New York in 1968:

"Jimi was very self-demanding and a perfectionist. So when he heard back this particular solo, he was understandably pissed off at the result. His expression reminds me of a gunslinger about to knock off his next opponent ... except that it would be Take 29 of the overdub solo!" -- Eddie Kramer

Hendrix works at the mixing board at the Record Plant in New York in 1968:

"Jimi was totally into the technology of the day as demonstrated by his ability at the board. We often mixed together as a team, mostly ending in very creative collaborations or falling over laughing at the mess we had made of the sound. In fact '1983 (A Merman I Should Turn to Be)' was mixed as one complete take with two or three rehearsals beforehand." -- Eddie Kramer

Hendrix works at the mixing board at the Record Plant in New York in 1968:

"Jimi was totally into the technology of the day as demonstrated by his ability at the board. We often mixed together as a team, mostly ending in very creative collaborations or falling over laughing at the mess we had made of the sound. In fact '1983 (A Merman I Should Turn to Be)' was mixed as one complete take with two or three rehearsals beforehand." -- Eddie Kramer

Hendrix at the Record Plant in 1968:

"Jimi had the habit of making the final draft of a song he was working on just before he went into the booth to record the vocal. This photo shows a smiling Jimi putting the final touches to 'Gypsy Eyes' from the many notes he kept with him usually written on hotel stationery, napkins or matchbook covers. These would be assembled on a yellow legal pad just prior to singing the final vocal. An interesting observation is that he wrote right-handed even though he played lefty." -- Eddie Kramer

Hendrix at the Record Plant in 1968:

"Jimi had the habit of making the final draft of a song he was working on just before he went into the booth to record the vocal. This photo shows a smiling Jimi putting the final touches to 'Gypsy Eyes' from the many notes he kept with him usually written on hotel stationery, napkins or matchbook covers. These would be assembled on a yellow legal pad just prior to singing the final vocal. An interesting observation is that he wrote right-handed even though he played lefty." -- Eddie Kramer

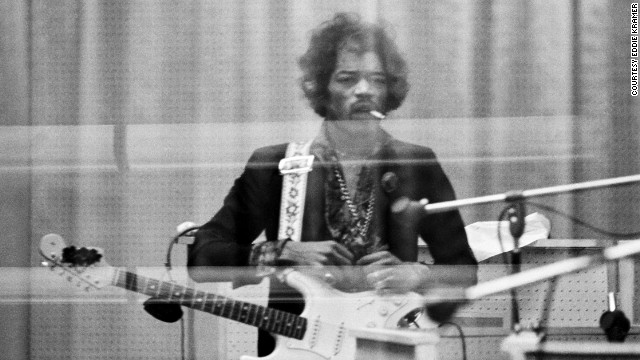

Hendrix records "Electric Ladyland" at the Record Plant in 1968:

"Even though Jimi smoked grass he was never too stoned to work diligently and with tremendous focus on the task at hand. He had just smoked a huge joint and was very happy and gave me a knowing smile, which I call the glint in the eye." -- Eddie Kramer

Hendrix records "Electric Ladyland" at the Record Plant in 1968:

"Even though Jimi smoked grass he was never too stoned to work diligently and with tremendous focus on the task at hand. He had just smoked a huge joint and was very happy and gave me a knowing smile, which I call the glint in the eye." -- Eddie Kramer

Hendrix and Buddy Miles at the Record Plant in New York in 1968:

"Jimi had a longstanding warm relationship with Buddy Miles. In this photo Jimi and Buddy can hardly contain their laughter. One of Jimi's most endearing traits was his amazing sense of humor. Even though it was at times self-deprecating, Mitch (Mitchell), Noel (Redding) and myself were often the butt of his jokes ... all in the desire to keep the sessions loose!" -- Eddie Kramer

Hendrix and Buddy Miles at the Record Plant in New York in 1968:

"Jimi had a longstanding warm relationship with Buddy Miles. In this photo Jimi and Buddy can hardly contain their laughter. One of Jimi's most endearing traits was his amazing sense of humor. Even though it was at times self-deprecating, Mitch (Mitchell), Noel (Redding) and myself were often the butt of his jokes ... all in the desire to keep the sessions loose!" -- Eddie Kramer

Hendrix records "Electric Ladyland" at the Record Plant in 1968:

"I have always loved this photo as it seems to sum up my feelings about the images I was privileged to capture. I am lucky enough to be sitting on the other side of the glass listening to a genius playing guitar and laying down take after take of fabulous history-making music, recording it for posterity and able to grab a shot of the artist deep in the middle of a take!" -- Eddie Kramer

Hendrix records "Electric Ladyland" at the Record Plant in 1968:

"I have always loved this photo as it seems to sum up my feelings about the images I was privileged to capture. I am lucky enough to be sitting on the other side of the glass listening to a genius playing guitar and laying down take after take of fabulous history-making music, recording it for posterity and able to grab a shot of the artist deep in the middle of a take!" -- Eddie Kramer