- Commercial music radio battles new technology, struggles for young listeners

- One station, Columbus, Ohio's WWCD-FM, saw changes and tragedy

- Industry is concerned about where new talent will come from

- The key, say some in radio, is to serve your community

"Do you remember lying in bed With your covers pulled up over your head Radio playing so no one can see ... " -- The Ramones, "Do You Remember Rock 'n' Roll Radio?"

Columbus, Ohio (CNN) -- In this capital city and college town, there is a shrine to a disc jockey.

His name was Andy Davis, better known as "Andyman," and he manned the evening drive-time shift at WWCD-FM. He was a bear of a man, a hugger, a backslapper, a preacher's son who called everybody "brother." He could carry you along with his enthusiasm.

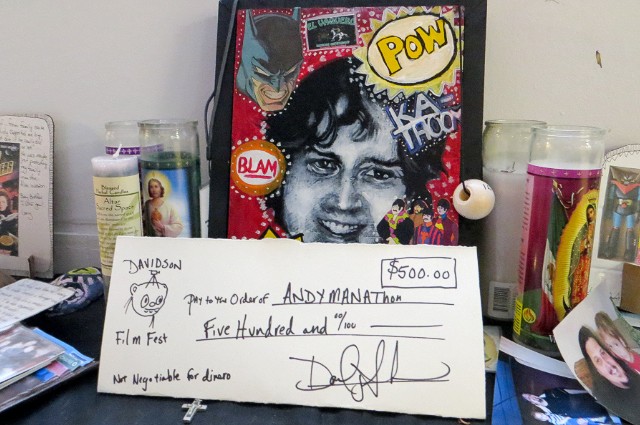

DJ Brian Phillips recalls Davis' annual 48-hour fundraising extravaganzas, known as "Andyman-a-Thons," exhorting callers to outbid one another. "Come on, brother, 10 dollars more!" Andyman would say.

"Our children's charities meant everything to him," Phillips says. "By the end of each Andyman-a-Thon, he was drained and everyone was in tears. He had given his all, and yet you'd have to drag him out of that studio."

He gave everybody a shot. Lesley James was a guest DJ -- an enthusiastic listener who once got to do an hour of her favorite songs on-air. When she was done, she nervously handed Davis her resume.

"(I) mentioned that I grew up listening to the radio station and wanted to be a part of it," she recalls. "He laughed, smiling at me and said, 'Honey, I don't need a resume. I like what I heard over the past hour.' "

He was an evangelist for local music. "I felt like Andy was someone who was looking out for a local musician just getting started and looking out for my best interests," says musician Brian Epp, who remembers Davis' support before a show.

"I will never forget his smile and that initial hug. When he announced us and said that he was from CD101, I felt like we were getting some rite of passage."

That was Andy. He was your friend.

On July 18, 2010, Andy Davis died. He was just 42.

His death hit everybody hard -- and shook the station to its core. WWCD was hanging on by its fingernails. The recession had ripped into revenues. The ratings were troubling. The station was going through a complex financial transaction: It had just sold its frequency, 101.1, to Ohio State University and was making arrangements to move up the dial to 102.5 in hopes of expanding its audience. The entire staff had taken a substantial pay cut. Even the lease on its office space was up.

In the midst of all this, here was Andy's wife, Molly, calling to deliver the awful news.

For a rare bird in an increasingly generic business -- a completely independent commercial music station -- it was going to be a struggle. WWCD had no safety net: It wasn't part of a regional "cluster" of stations, it had no TV or newspaper ties, there was no giant conglomerate to move money over from another division's pockets. Everybody's lives were wrapped up in the station.

Competition, the economy and now its beating heart: WWCD was at a crossroads, and the path ahead was full of static.

"During all that time, we had to make a decision on whether to keep the radio station," recalls Wendy Vaughan, wife of owner Roger Vaughan. "And my head said, 'You need to let it go.' But my heart said, 'This is a guy's life, his legacy, his identity, you can't let it go.' "

A medium in flux

"The world is collapsing around our ears I turned up the radio But I can't hear it ..." -- R.E.M., "Radio Song"

It wasn't just WWCD. Quietly in some markets, loudly in others, music radio has been under siege. Like many media, it's battling demographics and technology to stay alive, at the same time losing the institutional memory and talent that made it distinctive.

"Radio creates such a powerful connection," says Randy Malloy, who as general manager was trying to save the station with Roger Vaughan.

"You don't remember the newspaper article that you read when you had your first kiss or the TV show. It was a song. You remember that song. There's such a hard-wired connection in our brains to music."

Which is why people in the industry are worried that old-fashioned AM/FM radio may be drifting off into the ether, as it struggles to attract the young listeners who have been its bedrock for generations.

Sure, broadcast radio's been the redheaded stepchild of communications media for decades. TV, CDs, satellite, the Internet -- they were all supposed to kill it off.

Radio ad man Mark Lipsky jokes that he "keeps a black suit in my closet" for all the funeral announcements he's seen for the medium. He says radio remains strong and will adjust. It always has.

"AM/FM radio will probably command a smaller slice of the pie," says Lipsky, president and CEO of the Radio Agency. "But it's certainly not going to be replaced."

Others are less optimistic. The business is in flux. Rock music has fallen out of fashion. Format changes are common. The 12- to 24-year-olds who are the radio listeners (and employees) of the future are gravitating toward the Internet or iDevices. Three of the biggest hits of the last year -- "Call Me Maybe," "Gangnam Style" and "Harlem Shake" -- were driven by YouTube and social media. Billboard magazine, the chart bible, just added YouTube to its pop chart sources.

Clear Channel and Cumulus -- the two dominant radio broadcasters, each with hundreds of stations -- are struggling to pay off mountains of debt and have laid off thousands of workers, including many DJs.

And the heart of terrestrial radio -- its emphasis on the local -- has drifted. Hometown DJs, once the central voice of it all, increasingly find themselves marginalized in favor of syndicated voices and formulaic presentations.

That's a concern, says Lipsky. "Anybody can play Bruno Mars and Pink, but nothing's going to replace the sound of having a local jock tune you in to when (those artists are) coming to town -- things that make you part of your community."

Industry analyst Jerry Del Colliano, publisher of "Inside Music Media," says he believes the future is dim.

Radio, he warns, is no longer appealing to young people. "They don't like it, don't use it that much, don't know the stations, and at the same time the radio companies are shooting themselves in the foot by cutting back and getting rid of personalities."

He looks at the landscape and wonders about the attraction.

"If any of this is true, why would you want to be in this business?"

Ed Levine, whose Galaxy Communications owns a handful of stations in central New York State, puts it more bluntly.

"If we're not proactive, we'll be newspapers."

'God, disc jockeys, then parents'

"I'm in love with the radio on It helps me from being alone late at night ..." -- Jonathan Richman, "Roadrunner"

Andyman always wanted to be in radio.

A native of rural Ohio, he got the bug early, going to broadcasting school and working as an overnight jock at a country station. But WWCD was where he wanted to be, and he called the station incessantly, volunteering to work any shift, do any job.

"He finally wore them down," says Molly Davis, his widow.

He worked his way up from overnights and random shifts to become music director -- the person who manages the station's song selection -- and then program director, a job that oversees the station's entire on-air output, including DJs, music and commercials.

He was always sincere and passionate, says Tom Butler, one of his many protégés.

At the end of a summer festival, Butler recalls, "Andy was still standing at the gates, shaking hands with every single person who walked through. He just genuinely wanted to meet and connect with every single listener, every single fan."

It's the sort of enthusiasm one might associate with a different generation, when DJs were the "pied pipers of rock 'n' roll," and their distinctive voices were ubiquitous -- and powerful. In 1966, a Hollywood teen fair asked visitors about the biggest influences in their lives. The order: "God, disc jockeys, then parents," the late Robert W. Morgan, the leading voice of Los Angeles' KHJ, once recalled.

Of course, that was a different time, when Top 40 ruled and "everybody listened to the same stuff," says Allan Sniffen, who runs a website dedicated to New York's old WABC-AM back when it was "Musicradio 77."

Listen to the kings of radio: All-time great DJs

Nowadays, radio is more corporate and buttoned up, which has made DJing and programming a harder job. On the one hand, people complain that radio sucks -- it's generic and boring and the DJs all sound the same, the music all sounds the same, even the manic car commercials all sound the same.

On the other hand, new music and creativity can be tough sells. People like the familiar. The familiar is dependable, and dependable is easier to sell. The pressure at music stations is to stick with the tried and true, to run focus groups and test out the wazoo.

Margot Chobanian, former music director of Atlanta's now-defunct DaveFM, says the trend has been to cut back on DJs and their patter because ratings show that people don't like chatter.

She doesn't agree with that interpretation of the data though. What corporations don't understand, she says, is that the amount of DJ chatter has nothing do with tuning out -- it's the quality of what the DJs say.

"(People) were engaged by the DJs," Chobanian says.

Though Chobanian's bosses at CBS Radio gave the adult-alternative station a longer run than she expected, last fall, when the ratings declined, the station switched to sports talk and much of the staff got the ax.

Chobanian is leaving terrestrial radio behind. She now has a website called eavradio.com, a new-music station with an emphasis on the Atlanta scene.

"I see it as an extension of what DaveFM could have been," she says.

And old-fashioned broadcast radio? She's done -- done with the numbers, the restrictions, the suits.

"I'll never program for a corporate radio station again," she says.

Remaking the business

"Life is a rock But the radio rolled me ..." -- Reunion, "Life Is a Rock (But the Radio Rolled Me)"

At 15, Bob Pittman started as a DJ in his hometown of Brookhaven, Mississippi. It was not his first choice.

"I really wanted the high-paying job in town, which was bagging groceries at the Piggly Wiggly," he says.

Radio was, however, the right choice.

He was quickly promoted to positions up the line. By 1974, when he was 20, the "Boy Wonder" was the program director of WMAQ-AM in Chicago. Within three years, he was running WNBC-AM in New York, one of the biggest stations in the country.

Over the next three decades, he helped found MTV, became a successful producer, headed Time Warner's Six Flags theme parks division, ran the Century 21 real estate company, took over AOL in its formative years and was chief operating officer of the merged AOL Time Warner.

And then, three years ago, the famed media entrepreneur returned to his radio roots, investing $5 million in Clear Channel. Today he's head of the nation's largest radio company, becoming the symbol of "corporate radio."

Clear Channel chief: Technology 'an opportunity, not a risk'

While he was gone, there were plenty of changes. When Pittman started, music radio mainly used to be AM Top 40; over the years, it moved to FM on a continually splintering array of formats.

But the big sea change in the business came 17 years ago when Congress passed the Telecommunications Act of 1996. Gone were restrictions on the number of stations a company could own in a market; suddenly corporations went on a buying spree. The two biggest, Clear Channel and Cumulus, started dominating markets by purchasing several stations in the same city.

At its peak, Clear Channel owned more than 1,200 stations, a concert promotion company, a billboard division and a variety of other interests. (Before 1996, it owned 43 stations.) It's since sold off the concert firm, but still owns about 850 stations. Cumulus has about 570.

With Clear Channel's aggressive tactics and formidable clout, others in the business took to calling the company the "Evil Empire." Eric Boehlert wrote a number of stories for Salon about its power plays, calling it "radio's big bully."

For a decade, the big companies thrived, but the recession hit them hard. In 2008, Bain Capital helped lead a leveraged buyout of Clear Channel. The company now has $20 billion in long-term debt, and according to a 2012 article in Forbes, "barely earns enough to cover its interest payments and capital expenditures." Cumulus posted a huge loss last year thanks to its debt load.

In 2010, Pittman bought into Clear Channel, telling The Wall Street Journal he'd agreed to "help out part-time." A year later, he became CEO. He's been trying to remake it ever since.

It hasn't been easy. The company has been on a cost-cutting binge for several years, shedding stations, cutting jobs and consolidating operations. One of its practices, voice-tracking -- in which a DJ in one city can broadcast his or her show to several others, giving the appearance of a local broadcast in each market -- has been particularly criticized as emphasizing the national (and generic) over the local.

The cutbacks have taken a toll: Rick Wright, a longtime radio veteran and communications professor at Syracuse University, does a weekend show at a Clear Channel station. He says the building's local studios are like a ghost town when he visits.

Pittman dismisses the criticisms. The company still believes in local, he says, only now it's tapping into national talent -- the way local TV stations replaced their self-produced talk shows with "The Oprah Winfrey Show" nearly three decades ago. And the company's head count, he maintains, is still healthy.

"We have cutbacks, but you don't look at the other side of the equation, which is, how many people have we hired?" he says, his Southern accent mixing smoothly with his rat-a-tat-tat, statistic-laden delivery. "Our head count has not gone down as a company, and the reason it has not gone down is because we're constantly rebalancing."

Creating a 'trusted friend'

"There goes the last DJ Who plays what he wants to play ..." -- Tom Petty, "The Last DJ"

Roger Vaughan got the idea for WWCD after living in Denver in the 1980s while working in real estate.

He was inspired by KBCO, a station in nearby Boulder, Colorado, that played new music with the energy of old radio.

"I've had this love of both radio and music my whole life," he says. "I considered both businesses 'magical' and never even dreamed I might work in either. You needed some sort of special talent or something, right?"

Vaughan wondered if he could replicate something like KBCO in Columbus, where, he says, "radio sucked."

"I ... convinced myself that Denver and Columbus were similar demographically, that a radio adventure like this could both sound unique and be profitable and that I should try to do this," he says.

WWCD -- then CD101 -- went on the air in 1990.

Randy Malloy was there almost from the beginning. He moved to Columbus from college in New Jersey in the late 1980s, started at the station as an intern and worked his way up.

At 49, Malloy looks like an older version of Crispin Glover's grown-up McFly character in "Back to the Future": blond hair with bits of gray, lank and long on the sides and back, as if he'd gotten in an argument with his barber halfway through a haircut.

He talks fast and thinks faster, his voice a Mel Brooksian rasp trying to keep up with all the possibilities in his brain.

He's a one-man chamber of commerce for his adopted hometown.

On a gray winter's day he drives up High Street -- the Ohio capital's main drag -- and proudly points out sights: the reborn downtown, the once-dead Short North neighborhood, the Ohio State hangouts. He talks about the city's plans to get rid of the one-way boulevards that shuttle people to the suburbs; he praises the homes in German Village and hopes for growth in the nearby Brewery District. It's a gentrifying but still patchy area south of downtown by the Scioto River, the kind of place where you'd imagine an alt-rock broadcaster to take up residence.

Localness used to be the point of radio. It may have attracted its audience through the music, but it kept them by keeping them informed -- being a "trusted friend," as Malloy says.

Syracuse's Wright puts it more succinctly: "The greatest social media is radio broadcasting."

Wright remembers his godmother advising him on the importance of community. She hosted a popular midday show on WRAP in Norfolk, Virginia, that played music, conducted interviews and provided information.

"She told me, if you're ever really serious about putting a radio station together, you want your air personalities to become so integrated into the total sociological fabric of the audience that you're serving, that when they're in trouble, they'll call the disc jockey at the station before they'd call the police," he recalls.

"You've become part of the family. They feel they know you."

'Rock local'

"It blows a hole in the radio When it hasn't sounded good all week ..." --The Clash, "Hitsville UK"

It took a lot of effort after Andyman died, but WWCD stayed on the air.

Vaughan plowed in more money. Malloy sank his 401(k) into buying a majority interest. The station redoubled its marketing efforts, particularly partnerships with a local music promoter and Columbus' pro hockey team, the Blue Jackets. Everybody took pay cuts and multitasked, with DJs doing promotions and interns doing everything.

WWCD is a throwback. It's one of just a handful of independent, major-market commercial music stations left in America. It's run like a throwback, too, with a strong focus on new music and community service.

Indeed, the station flaunts its indie credibility like a bold tattoo. "We're not Clear Channel," trumpets the station's on-air IDs -- a shot at its powerful competitor, which owns six Columbus stations, including the market leader. A CD file drawer in the studio sharpens the point with the bumper sticker "Clear Channel Kills." "Rock local," adds a banner on its website.

Radio's last stand: A day in the life at CD102.5

There's a lot of bad blood between Clear Channel and others in the industry, thanks to the former's tactics in the early 2000s. Malloy and the Vaughans talk about Clear Channel's dominance with an attitude bordering on disgust; Wendy Vaughan says the company offered $15 million for the station at one point.

WWCD's studio and offices form a ramshackle warren of rooms in the basement of a renovated restaurant and reception hall in the Brewery District. Fittingly, the dominant feature is a large bar complete with an ice-cream freezer. ("We're a bar with a radio problem," Malloy jokes.)

Decorations around the studio window wish patrons a happy holiday -- changing with the season. Inside the studio are wooden slat seats from the old Cleveland Municipal Stadium. A mannequin wearing a skull mask and black robes keeps watch over an equipment closet. There are about a dozen employees ambling about, some dressed so casually it's hard to tell the veterans apart from the college-student interns.

The station van, an old ice-cream truck, is parked outside. Malloy, a DIY-type guy who drove an ambulance to put himself through college, has been spotted covered in motor oil from trying to get it started.

The vibe is that of a low-key clubhouse.

A number of employees talk about growing up with the station and say that working there is a dream come true. Kyle Hofmeister, one of the DJs, grew up near Columbus but spent his college years in Florida.

"One of the big things about leaving town was I realized how much I missed this particular radio station," he says.

"We have kids who tell us, 'I grew up listening to you,' and now they've started a band, and now their goal is to get on the 'Top 5 at 5,' " Malloy says. "They're excited, and that excites us."

On a recent Tuesday morning, the DJs and interns pour into Lesley James' narrow office for their weekly music meeting -- a kind of rate-a-record free-for-all for new releases.

That one-hour guest DJ whom Andyman hired without seeing her resume is now the station's program director -- taking over after Davis died.

The music meeting is open to pretty much any staffer. As in Andyman's day, anything is fair game; record labels drop off new records all the time, but if a listener records a song in his dorm room and sends over the MP3, the gang will give it a go.

Tom Butler, the evening-drive DJ who shares an office with James, pops in record after record: the Dirty Projectors, Thao with the Get Down Stay Down, Grizzly Bear.

A new cut by the French turntablists C2C earns wildly different reviews: "It's innovative ... if that's what you're going to call it," says one staffer. Johnny Marr, the former Smiths guitarist, fares better with his latest.

Through it all, James scans Facebook, goes over playlists and takes notes. She lets the group offer their take and then she offers her opinion with a firm politeness that suggests she can hear whether the song fits with the station's overall feel.

Which is not to say that CD102.5 doesn't experiment. Its playlist includes more than 40 slots for new releases -- a huge number in the play-it-safe world of commercial radio. And James is aggressive: When the new David Bowie single was released, she didn't wait for a handout but paid the buck to download it from iTunes. It's not an unusual occurrence.

"We're a new music station," she says. "We love to break bands."

Among the groups that have used WWCD as a launching pad have been the Lumineers, Fitz and the Tantrums, the Black Keys and Mumford & Sons.

WWCD also likes to support the local community -- a connection that goes both ways, Malloy says. CD102.5 has been voted the city's best radio station in a local poll for almost two decades straight.

"We believe we make the city better," Malloy says.

The station offers "stress breaks," handing out treats from its ice-cream truck, maintains a "Green Team" beautification squad, participates in arts festivals and still engages with residents through the Andyman-a-Thon.

Jami Goldstein, vice president of marketing for the Greater Columbus Arts Council, says the station goes above and beyond.

"Other stations do provide promotional support but don't go the distance like CD102.5 does," she says.

"For a community to be truly vibrant culturally, you need to have really good institutions, access to great events and support for individual artists. The great thing about 102.5 is they help in all three areas."

Talent and technology

"So get off the wall, become involved All your radio problems have now been solved My treacherous beats make ya ears respond And my radio's loud like a fire alarm ..." -- LL Cool J, "I Can't Live Without My Radio"

Does anyone dream of owning a radio station anymore?

When I was in my teens and early 20s, my friends and I would fantasize about winning the lottery and buying a crappy AM signal. (An FM signal would be fine, too, but we figured it would be too expensive.)

Our model was a cross between the AM greats and the free-form FM stations, in which the DJs would be energetic, fun and a little off-color, and the music would be a mix of ... well, whatever tickled our fancy. It would be exciting, it would be rhythmic and fluid and honest, and we'd always tell listeners the names of the songs and artists they'd just heard.

If I were in college today, would I even dream of working at a radio station -- much less owning one?

"I don't think there is a living to be had in (radio)," says Ana Zimitravich, a student at Georgia State University and general manager of its new-music oriented WRAS-FM. "It is a slowly dissolving business."

Her colleague, WRAS music director Fray DeVore, says that's true for much of the staff, including himself. The Georgia State students they cater to in Atlanta are partial to the Web.

"Now we have a culture of blogging. That's how a lot of (musical) exposure is going on now, through the Internet," DeVore says. "There are so many other resources available than getting in your car and turning on the radio."

Opinion: Who needs radio? I'll take the Web

The high school and college kids who once craved radio employment -- and trained on their college or local stations -- are finding it harder to get jobs, thanks to the elimination of air shifts. The farm system has been devastated.

"In the old days, if you were a (communications) major or just anybody who was interested in getting into radio, you could find a small- or medium-market radio station and you learned your craft," Syracuse's Wright says. "Now you go into a radio station and there is nobody there. Nobody. There's a computer running the place."

Wright blames the industry leaders.

"The guys who really own this industry are trying to run it as cheap as they can, and that means not hiring any people," Wright says. "And in the meantime they're not laying any seeds for the future of the industry."

Clear Channel's Pittman admits his primary focus now is technology.

One of Clear Channel's major new ventures is IHeartRadio.com, a Web service that features "1,500+ live stations or create your own," its website says, including a Pandora-like channel and several programmed playlists. It's available on the Web or through a variety of device platforms, including apps for iPods, Androids and Kindles.

The idea is to get more stations into more places, whether it's through the Internet or portable device apps. Public transit commuters, for example, can plug into IHeartRadio.com through their smartphones, or people in one market can listen to stations in others.

"What we want is to find more listening occasions," Pittman says.

Digital listening is currently less than 10% of the radio audience, according to a 2012 Pew Research Center survey, but Pittman expects it to be a major part of the future.

"In terms of the digital revolution, we're way behind, but we think it's a terrific opportunity for us," he says.

But others call out the clash between Clear Channel's digital plans and its local cutbacks.

"What he says sounds really good. What he does, not so good," says Galaxy Communications' Levine. "He talks about content over here and when you're not looking, lays off 700 people over here. And nobody calls him on it."

He says IHeartRadio will be stillborn without investing in talent and stations.

"(The) IHeartRadio app is not content," he says. "You need living, breathing people to drive this thing called content, and if you keep systematically firing them, like Clear Channel and Cumulus do, you're not going to have much of an industry left."

Del Colliano, the radio analyst, is even harsher: "He's not there at Clear Channel to turn it around. He's there to do what he's done best in the prime part of his life, which is to find a way to package the company so it can be sold to someone else."

A recent post on Del Colliano's site maintains that Clear Channel will start selling off its lesser market stations in about a year and offer the buyers a Clear Channel product called "Premium Choice," featuring voice-tracked talent.

Clear Channel dismisses Del Colliano's criticism. "Jerry Del Colliano's blog is less a tip sheet than a fantasy," says a spokeswoman. "He's been 'predicting' things for years that don't happen and have no basis in reality."

Del Colliano is a pessimist about broadcast radio. Pittman looks at Clear Channel as an "opportunity."

"When people call you an evil empire, what they're saying is, you're not doing anything new and exciting. And I think the opposite side of having a big platform to play with is you can do great stuff," he says, reeling off charitable initiatives, indie band programs and other digital projects.

"That's the exciting thing about being a big platform. The unexciting thing is if we were dull and boring and did what we did 10 years ago or 20 years ago."

'We are so plugged in'

"There is magic at your fingers For the spirit ever lingers ..." -- Rush, "The Spirit of Radio"

Things are looking up in Columbus. The recession is fading and sales are improving. Thanks to the new signal, WWCD's ratings are up as well -- in March it posted its best overall audience numbers in at least three years, with strong showings in key demographics -- and the staff believes the community is behind them.

"We are so plugged in to this community. If we went away, people would definitely notice," says Phillips, a DJ who's been with WWCD for 18 years. "It's the personal touch that's been completely lost from radio. ... Obviously, this is a business, but we're always thinking, how can we be more involved in the community?"

It could be for naught, of course. Del Colliano is fond of a metaphor to describe good, profitable, well-run stations in the current media environment: They're like beautiful estates in the middle of a slum.

"(In radio) you can be a good operator," he says, "but the majority of the real estate is blighted by companies that don't care."

Lipsky, the radio agency head, doesn't buy into the doomsaying. Radio's not going any place; it'll just be another platform, he says, "a wonderful conduit that still keeps you connected."

At CD102.5, the staff chooses to look at the bright side.

Malloy, who started out in the promotions department, is always coming up with new ideas; the latest is a television reality show based on the station called "Life On Air." He's had a reel produced and is trying to interest a network in picking it up.

He prefers another metaphor to Del Colliano's, of big box stores and a local hardware retailer. There's no reason both can't thrive.

"I love Lowe's. I love Home Depot. They serve a purpose for me. But I also love Zettler Hardware," he says. "Because when I know exactly what I need, I know I can go to Zettler Hardware and they'll have it. And someone's going to meet me at the door and go, 'Can we help you with something?' And they walk me over to it, they show me the product, I purchase the product and I walk out happy. That's what we are. We're Zettler Hardware."

The shrine to Andyman is just a few steps from WWCD's studio -- a table lined with candles, photos and a mock check for the Andyman-a-Thon. In the center, there's a portrait of Andy Davis.

His spirit is always present: the spirit of a big-hearted man, the spirit of music radio.

Malloy remembers a time long ago. It was his first day at the station, and he was at an event, walking across a field. The ice-cream truck pulled up. Inside was Andyman.

"Get in," the DJ said. "Let's go!"

Andyman may be gone, but the station rolls on.

Radio host Rachael Gordon talks on-air from the CD102.5 studios in Columbus, Ohio.

Radio host Rachael Gordon talks on-air from the CD102.5 studios in Columbus, Ohio.  People line up to attend one of CD102.5's

People line up to attend one of CD102.5's  Super fans Kathy Thrush, left, and Carissa Thrush say they try and make it to the station's Big Room concerts regularly.

Super fans Kathy Thrush, left, and Carissa Thrush say they try and make it to the station's Big Room concerts regularly.

Randy Malloy, CD102.5's president and general manager, chats with marketing director Kara Jones in his office. The station, which isn't part of a larger media corporation, has been independently owned and operated for more than two decades.

Randy Malloy, CD102.5's president and general manager, chats with marketing director Kara Jones in his office. The station, which isn't part of a larger media corporation, has been independently owned and operated for more than two decades.

Bands that perform at the station leave their mark on walls around the Big Room.

Bands that perform at the station leave their mark on walls around the Big Room.

The Neighbourhood, an indie pop band from California, performs live at the Big Room.

The Neighbourhood, an indie pop band from California, performs live at the Big Room.

CD102.5 program director Lesley James shoots video with her phone while the Welsh alternative rock trio the Joy Formidable plays.

CD102.5 program director Lesley James shoots video with her phone while the Welsh alternative rock trio the Joy Formidable plays.

Members of the Neighbourhood warm up before their Big Room performance.

Members of the Neighbourhood warm up before their Big Room performance.

Fans fill the Big Room to watch the Neighbourhood perform. The station regularly gives away passes to listeners.

Fans fill the Big Room to watch the Neighbourhood perform. The station regularly gives away passes to listeners.

Staffers and interns play darts during some downtime on the weekend shift at CD102.5.

Staffers and interns play darts during some downtime on the weekend shift at CD102.5.

A Moby platinum record adorns one of the walls at the station.

A Moby platinum record adorns one of the walls at the station.

A U2 poster and other band memorabilia hang above an ice-cream cooler near the station's entrance.

A U2 poster and other band memorabilia hang above an ice-cream cooler near the station's entrance.

DJ Nate and Krista Kae introduce local band Post Coma Network, the opening act for the Second Dose of the CD102.5 Day concert series on April 6 at the Lifestyle Communities Pavilion in Columbus. The station supports local artists.

DJ Nate and Krista Kae introduce local band Post Coma Network, the opening act for the Second Dose of the CD102.5 Day concert series on April 6 at the Lifestyle Communities Pavilion in Columbus. The station supports local artists.

Fans watch Australian band San Cisco perform at the CD102.5 Day concert.

Fans watch Australian band San Cisco perform at the CD102.5 Day concert.

A concertgoer cools off with a CD102.5 fan. The station's staff members say they believe the community is behind them.

A concertgoer cools off with a CD102.5 fan. The station's staff members say they believe the community is behind them.